Governance Policies and Political Landscapes in the Southern Levant under the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Aree / Gruppi di ricerca

Partecipanti al progetto

- Palmisano Alessio (Responsabile)

- Andrea Titolo (PostDoc)

- Karen Radner (Collaboratore)

- Jamie Novotny (Collaboratore)

Descrizione del progetto

A large part of the human population in world history lived under imperial rule (Goldstone and Haldon 2009). Imperial policies had a remarkable impact on the subjected landscape and the communities and some scholars argue that the legacy of ancient empires persists in the modern world (Bernbeck 2010; Hardt and Negri 2000). How did empires shape political landscapes? What was the impact of changes in human population upon rural land-use intensity? How did this pressure drive the transformation in the existing local social institutions, and how did this vary regionally?

This Gerda Henkel Stiftung funded project aims to provide answers to these questions using two widely available sources of data, namely archaeological records and written sources.

This Gerda Henkel Stiftung funded project aims to provide answers to these questions using two widely available sources of data, namely archaeological records and written sources.

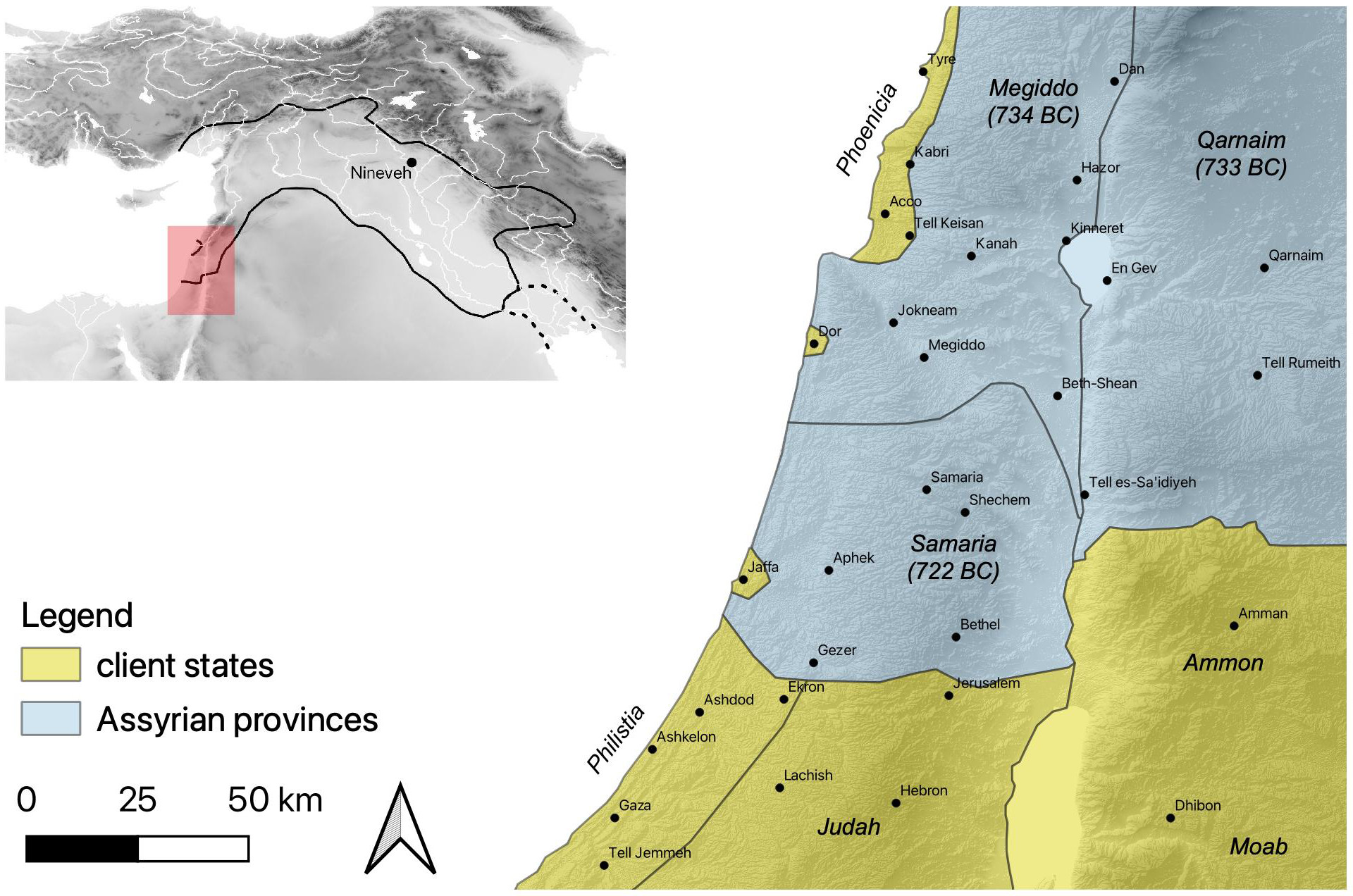

The Assyrian Empire reached its apex in the 7th century BC when it stretched from the Egyptian Delta to the Caspian Sea, as a result of an expansionist policy begun in the early 9th century BC, under the king Aššurnasirpal II (ca. 883–859 BC). The Southern Levant constituted the southwestern edge of the Neo-Assyrian Empire; it represents an excellent case study to investigate in a long-term perspective given that it incorporated diverse socio-ecological contexts and experienced the rise and fall of regional kingdoms and the domination by vast Empires between ca. 1500 and 330 BC (e.g., Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian). In the Iron Age (ca. 1150–586 BC) the region encompassed the kingdoms of Israel, Judah, Ammon, Moab, Edom, the Philistine and Phoenician city-states and a part of the kingdom of Aram Damascus (Fig.1). The kingdoms of Israel and Aram Damascus were completely conquered and turned into Assyrian provinces by the late 720 BC, while the other kingdoms became client states (Becking 2019; Novotny 2019). As a consequence, the southern Levant was directly (as a province) or indirectly (as a client state) under the Assyrian rule for approximately a century between ca. 734 and 640 BC.

Figure 1. Southern Levant during the Assyrian rule (ca. 734–640 BC). In brackets is the date of the establishment of the Assyrian provinces.

Figure 1. Southern Levant during the Assyrian rule (ca. 734–640 BC). In brackets is the date of the establishment of the Assyrian provinces.

A growing recent literature has emphasized how imperial strategies were nuanced and vary from region to region and depending on political circumstances (Düring 2020; Faust 2021; Parker 2020). These studies have recognised that centrally planned imperial policies heavily transformed cultural and physical landscapes and the establishment of new small rural settlements in areas previously underpopulated (a phenomenon also known as “landscape infilling”) was also the result of forced internal migration fostered by the Assyrian central authority to quell particularly rebellious regions (Radner 2016), to boost a uniform Assyrian culture (Parpola 2004) and to increase the intensity of agricultural production (Radner 2000; Rosenzweig 2016).

This planned two-year project will make use of a holistic approach integrating archaeological, textual and geographical data into a spatial framework to have a better understanding of the Assyrian imperial policies occurring in the region. Unlike the patchiness in the archaeological dataset in the Assyrian heartland and the northern frontier of the empire, the Southern Levant is a privileged area for the study of Assyrian imperialism given that likely has the largest archaeological dataset in the world (hundreds of archaeological excavations and detailed surveys) augmented by a relatively large number of textual evidence found both in the region and Mesopotamia (e.g., Assyrian royal inscriptions, administrative documents and correspondence relating to the region). In addition, this area is characterised by a variety of different polities (e.g., Assyrian provinces, client states) requiring the implementation of a wide range of governance strategies by the imperial Assyrian administration to maintain and consolidate its power in the area. Therefore, for the first time, this project will systematically analyse the unparallel information from the region to avoid any misinterpretation due to partial use of the disposable data and to shed new light not only on the Assyrian governance policies but also on the local responses to the imperial activity.

PROJECT TEAM

Alessio Palmisano (Principal investigator) is a Senior Assistant Professor of Methods for Archaeological Research at the University of Turin. His research has been primarily centred on the development and application of bespoke quantitative and computational methods to Archaeology. He applies these approaches to address a variety of research topics, including settlement patterns, long-term human-environment interactions, population dynamics, and long-distance cultural contacts and trade. He took part, with roles of scientific responsibility, in several campaigns of archaeological fieldwork, primarily in Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Italy. He has also been working on the project "The Empire Strikes Back: the Geography of Governance Strategies in the Assyrian Empire" funded by the Rita Levi Montalcini Programme for early career researchers.

Alessio Palmisano (Principal investigator) is a Senior Assistant Professor of Methods for Archaeological Research at the University of Turin. His research has been primarily centred on the development and application of bespoke quantitative and computational methods to Archaeology. He applies these approaches to address a variety of research topics, including settlement patterns, long-term human-environment interactions, population dynamics, and long-distance cultural contacts and trade. He took part, with roles of scientific responsibility, in several campaigns of archaeological fieldwork, primarily in Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Italy. He has also been working on the project "The Empire Strikes Back: the Geography of Governance Strategies in the Assyrian Empire" funded by the Rita Levi Montalcini Programme for early career researchers.

Andrea Titolo is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at University of Turin and is currently working as member of the project “Governance Policies and Political Landscapes in the Southern Levant during the Neo-Assyrian Empire”. His research so far has been focused on the study of South Western Asian Iron Age settlement patterns, namely along the Euphrates River, through quantitative and computational methods; he also studied the archaeological landscape through multidisciplinary approach, while also focusing on developing reproducible and open-source remote sensing methods for assessing and monitoring the resurfacing cultural heritage. He also took part, with roles of scientific responsibility, in several campaigns of archaeological fieldwork, primarily in Iraq, Lebanon, and Georgia.

Andrea Titolo is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at University of Turin and is currently working as member of the project “Governance Policies and Political Landscapes in the Southern Levant during the Neo-Assyrian Empire”. His research so far has been focused on the study of South Western Asian Iron Age settlement patterns, namely along the Euphrates River, through quantitative and computational methods; he also studied the archaeological landscape through multidisciplinary approach, while also focusing on developing reproducible and open-source remote sensing methods for assessing and monitoring the resurfacing cultural heritage. He also took part, with roles of scientific responsibility, in several campaigns of archaeological fieldwork, primarily in Iraq, Lebanon, and Georgia.

KEY COLLABORATORS

Karen Radner (PhD University of Vienna) holds the Alexander von Humboldt Chair of the Ancient History of the Near and Middle East at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Her research focuses on the Assyrian Empire. A member of the German Archaeological Institute, of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities and of Academia Europaea, she was awarded the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize in 2022. Her numerous books include Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2015), A Short History of Babylon (Bloomsbury, 2020) as well as editions of cuneiform archives from Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Karen Radner (PhD University of Vienna) holds the Alexander von Humboldt Chair of the Ancient History of the Near and Middle East at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Her research focuses on the Assyrian Empire. A member of the German Archaeological Institute, of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities and of Academia Europaea, she was awarded the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize in 2022. Her numerous books include Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2015), A Short History of Babylon (Bloomsbury, 2020) as well as editions of cuneiform archives from Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Jamie Novotny is a tenured academic researcher of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for the Ancient History of the Near and Middle East at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Codirector of the Munich Open-Access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative (with Prof. Dr Karen Radner), and Editor-in-Chief of the Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Empire" (RINBE) project. He is the author, editor, or coauthor of several books, including The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626–612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Parts 1–3 and The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon.

Jamie Novotny is a tenured academic researcher of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for the Ancient History of the Near and Middle East at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Codirector of the Munich Open-Access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative (with Prof. Dr Karen Radner), and Editor-in-Chief of the Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Empire" (RINBE) project. He is the author, editor, or coauthor of several books, including The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626–612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Parts 1–3 and The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon.

REFERENCES

- Becking, B., 2019. How to Encounter an Historical Problem? “722–720 BCE” as a Case Study. In: S. Hasegawa, C. Levin, and K. Radner (eds.), The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 17-32.

- Bernbeck, R. 2010. Imperialist Networks: Ancient Assyria and the United States. Present Pasts, 2, 30–52.

- Düring, B.S., 2020. The imperialisation of Assyria: an archaeological approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Faust, A., 2021. The Neo-Assyrian Empire in the Southwest: Imperial Domination and its Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goldstone, J. A., and Haldon, J. F., 2009. Ancient States, Empires, and Exploitation: Problems and Perspectives. In: I. Morris and W. Scheidel (eds.), The Dynamics of Ancient Empires. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–29.

- Hardt, M., and A. Negri, 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Novotny, J., 2019. Contextualizing the Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel: What Can Assyrian Official Inscriptions Tell Us? In: S. Hasegawa, C. Levin, and K. Radner (eds.), The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 35-53.

- Parker, B. J., 2020. Re-modeling Empire. In: Boozer, A.L., Düring, B.S. and Parker, B. J. eds., 2020. Archaeologies of Empire: Local Participants and Imperial Trajectories. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Parpola, S., 2004. National and ethnic identity in the Neo-Assyrian empire and Assyrian identity in post-empire times. Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 18(2), 5-22.

- Radner, K., 2000. How did the Neo-Assyrian king perceive his land and its resources? In: R. M. Jas (Ed.), Rainfall and Agriculture in Northern Mesopotamia. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, 233-246.

- Radner, K., 2016. Revolts in the Assyrian Empire: succession wars, rebellions against a false king and independence movements. In: J.J. Collins, and J.G. Manning (Eds.), Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Leiden: Brill, 41-54.

- Rosenzweig, M.S., 2016. Cultivating subjects in the Neo-Assyrian empire. Journal of Social Archaeology, 16(3), 307-334.